Dark Earth: Beginnings

My novels, Ghostwalk, The Coral Thief and now Dark Earth, have rumbled slowly into life. Sometimes in the process several discoveries collide. Sometimes there are a series of what feel like fated collisions, what the great psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, might call ‘synchronicity.’

Nothing prepared me for the set of strange conjunctions that came my way between 2012 and through into 2018.

In 2012, my friend Ed, a keen horseman and Cambridge scholar of seventeenth-century literature, asked me if I wanted to join him and some friends on a trip across Jordan. Though the other three in our party were considerably younger and fitter than me, I jumped at the chance.

We flew into Oman in the north and then drove a hire car down through the length of the country to the great ruins of Petra in the south and then on to the Wadi Rum desert, where Ed had arranged with Bedouin guides to take us across the desert on horseback for five days. On the long car journey south, where a tyre burst on our car, forcing us to find a repair in a tiny village, we came across the ruins of Roman towns, rising through the sand, most not fenced off, some with Roman streets and shops and temples and colonnades still intact, right next to, or abutting, modern day towns.

We swam in the Red Sea. At most checkpoints we saw armed guards. When we got to the south of the country, we had six days in the Wadi Rum desert riding across the red sand with Bedouin guides. My horse, no doubt aware that I was an inexperienced rider, threw me on the first day, which gave me whiplash. For the following three days the Bedouin driver of the jeep and the journey cook, Saleem, took me in his jeep to meet his relatives up in the Bedouin camps. During this time, the ruins I had seen, the murals, the fragments of painted walls, began to haunt me.

A year later, in 2013, living in London, I visited the extraordinary British Museum Pompeii exhibition. I revisited five times, each time imagining more vividly a bustling Roman town through these haunting and evocative remains. I am still haunted by the charred cot, the remains of bread and chickpeas, the statues, the beautiful murals of birds on walls, the little family that had been incinerated, literally thrown apart as they tried to hide from the ash cloud and fire.

In 2018, as I began to write about Blue and Isla, my sixth-century protagonists, my daughter Hannah, then only 24, had the break of her early career as an actress. She auditioned to do an 18-month run in the Roman Season at the Royal Shakespeare company. She got the job. She was given a cottage to live in across the road from the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford.

In those 18 months I went to stay with Hannah often. She was playing leading female roles in three of the four Shakespeare Roman plays: Julius Caesar, Titus Andronicus and Corialanus. When she returned to London after the season finished, she landed the part of Octavia in the Ralph Fiennes and Sophie Okinado National Theatre production of Antony and Cleopatra – so she was now a rare actress, having played leading female parts in all four of the Roman Plays on major British stages.

In each each of these plays, Hannah played the part of a woman, daughter or wife caught up in a cycle of vicious male blood feuds and suffering. She was always playing the part of a pawn in the violent games of men: Lavinia in Titus, Virgilia in Corialanus, Portia in Julius Caesar and later Octavia in Antony and Cleopatra. It was especially heartbreaking to see her raped and mutilated on the Royal Shakespeare stage in Titus Andronicus, in front of an audience of a thousand people, covered in blood, her tongue cut out, her arms cut off. Her rapists had used her as a way of taking revenge on her father. I wept each time I saw it. Night after night, audience members fainted and had to be carried out.

When I visited Hannah in her RSC cottage during rehearsals, we talked about how she could find agency and dignity playing these terribly abused women and what alternative ways those women might have found to exercise their power. We played around with alternate history as a way of thinking about different, less brutal, outcomes for the women she was playing. It was interesting, but it also helped me to think my way into play, acting and games as a way of getting out of dangerous and brutal situations.

The acting/conjuring side of Blue is very much based on Hannah. On several situations she has got the two of us out of impossible - and, in one case, an extremely dangerous situation - as a very young woman by putting on a fake voice and pretending to be someone she wasn’t…

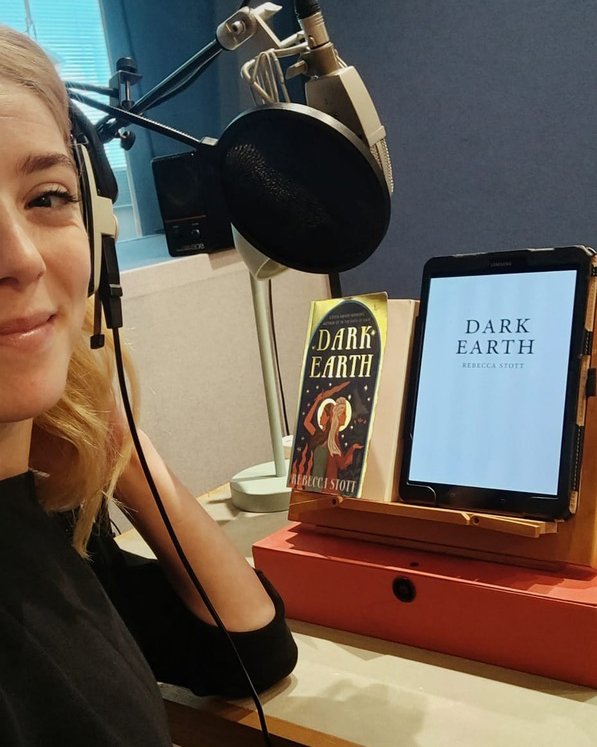

So when the publishers of Dark Earth asked me to suggest names for actors who might read the audio book, I suggested Hannah. She knew the book. She knew its gestation, how much had come from our conversations about her work on the stages of the National Theatre and the Royal Shakespeare Company, and the conversations we had had about women who are furious, thwarted and gifted. I know how gifted she was at conjuring voices and magic - she had been doing it since she was six. The publishers agreed. When Hannah finished recording the book in the studio at ID-Audio in May 2022, she texted me: ‘I gave myself the chills today,’ she wrote.

Listening to her version of the book on the audio recording made me feel that something from the sands of Jordan, and the British Museum and the stages of the National Theatre and the RSC Theatre - seemed to have come full circle.