Dark Earth

The mysterious black soil that covers the remains of Roman Londinium and other Roman cities (and the title of my novel)

I promised readers some background into the research I did for this book and some tales about some of the rabbit holes – research always involves rabbit holes – that I disappeared down, sometimes for months at a time.

This one is about soil, one of the starting points of my research, and one of the most mysterious aspects of the history of Roman Londinium.

I went to a lecture about Londinium in or around 2015 at the Museum of London. The lecturer talked about the hundreds of years after the Romans left Britain in c420AD in which Londinium, the mile-wide stone Roman city, lay empty, stone crumbling. Archaeologists believe the ghost city may have been empty for perhaps 400 years before it was reoccupied in the ninth century.

Why did no one go in? Neither the native Britons nor the Saxon, Jute or Anglii incomers arriving from what is now northern Europe had any use for the crumbling stone buildings. They built their houses in wood. It may also have represented to them the symbol of a fallen occupying power. They may have felt it was haunted.

The thought of that ruined city fascinated me. Bathhouses. A forum. Warehouses. Wharves. An amphitheatre. Villas and mosaics. Abandoned.

Something else grabbed my attention in that lecture. The lecturer referred to the ‘dark earth’ that archaeologists now find lying like a thick blanket forming the layer where Londinium had once stood, the layer under medieval London. Dark earth, dark ages, dark side of the moon. I was on the edge of my seat.

I spoke to her afterwards. ‘Dark earth’, I said, tentatively. ‘Is anyone still working on that?’ She laughed. ‘Finished a few archaeologists off back in the 80s,’ she said. ‘Ended a few careers. No one could get anywhere with it. No one wants to talk about it now.’

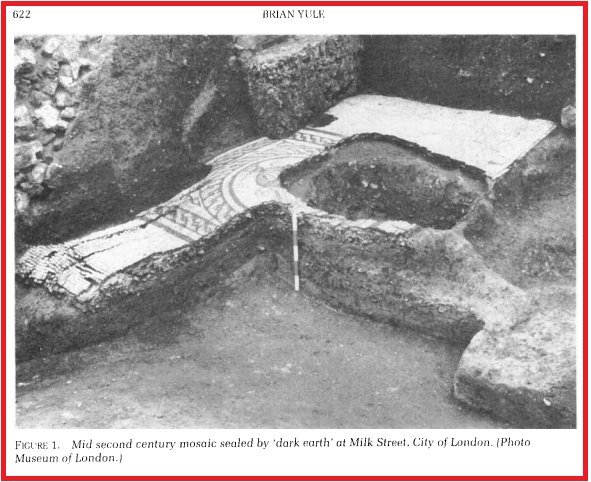

Confused? So was I. When I started reading, I discovered that essentially the great city of Londinium is now compacted down to a layer of black, organically rich, charcoal soil in some areas as much as 2m thick. It has seeds in it, pollen etc, but not much else. Of course, there are stubs of a mosaic floor here and a wall there, but where did all that stone go?

Back in the 80s when those archaeologists were fascinated and tormented by dark earth, when some of those careers came to an end, people had all kinds of theories about how it had formed. It was a conundrum. It kept some archaeologists awake at night. I sympathised.

Some people proposed that the Britons and the incomers from across the sea who lived and farmed around the ghost city dumped their waste there. But why would you go into a ruined city to dump your waste?

More bizarrely perhaps, others proposed that the Britons and incomers farming close by had used hand carts to carry rich soil into the city so that they could plant market gardens in the ruins. But why would you do that?

And given that dark earth is a layer of soil found blanketing other Roman ruins across the world, I found some other bizarre theories deep in Google layers. One of them proposed that there had been a tsunami or comet collision in the 5th century that had produced the layer…

With the help of the generous and inspiring Roy Stephenson, then curator of the Museum of London, I tracked down some of the people who had given up archaeology back in the 80s after working on dark earth. I went to visit some of them, travelling quite long distances. I was hooked.

‘I don’t like to think about dark earth anymore,’ one of them told me, searching out his old files, nonetheless. He explained about the politics of archaeology in London in the 80s, how hard it was to go against prevailing or entrenched theories.

The answer for him he said, lay in abandoned buildings in bomb-wrecked Berlin, studied by German urban ecologist Herbert Sukopp in the 1970s. Over fifty years, fallen leaves compacted down inside ruined walls, forming a dense compost heap. Imagine that heap after 400 years…

In such conditions a specific type of worm called Enchytraeidae, thin maggot-like worms which inhabit waste ground and soils in very great numbers, would have gone to work.

Londinium, the northernmost trading outpost of a great empire, once razed to the ground by the mighty Boudicca, but risen again and then walled, and then 300 years later abandoned, had been compacted down to a blanket of dark soil by worms…

It made me think of the great poem ‘Ozymandias’ by Percy Bysshe Shelley, published in 1818, in which Shelley imagines a traveller in an ancient land coming across ‘two vast and trunkless legs of stone’ in the desert and near them a ‘shattered visage’.

‘And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.’

So when I started to write my novel about two sisters on the run in sixth-century Britain who take refuge in the ruins of Londinium and find a community of looters living there, digging for material they can reuse or trade, I had to call it Dark Earth after this loamy, mysterious soil.

If you want to read more about ‘dark earth’:

Macphail, R. I. Galinie, H. Verhaeghe, F. (2003) ‘A Future for Dark Earth?’, in Antiquity, vol. 77; part 296, pp.349-358.

Watson, B and others (1998), ‘”Dark earth” and urban decline in late Roman London’ in Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1998, pp.100-106.

Brian Yule (1990), ‘The “dark earth” and Late Roman London’ in Antiquity, vol 64, pp.620-28.